Ertech founder Jim Giumelli is the driving force behind a training academy helping at-risk or disadvantaged students get into the workforce.

Fifteen years ago, Jim Giumelli volunteered at a fundraiser for Gerard Neesham’s Clontarf Foundation.

With a group of business leaders in civil contracting, he raised about $80,000 for the up-and-coming charity, which aims to improve the education and employment prospects of Aboriginal teenagers.

The funding was greatly appreciated but Mr Neesham wanted more.

“He said: ‘We don’t just need money, we need apprenticeships. Can you guys give us apprenticeships?’,” Mr Giumelli recalls.

“There was no such thing as an apprenticeship in our industry, but I thought we could establish a traineeship, with a simulated construction site and teach people how to drive machines and lay pipes, and so on.”

That was the genesis of the Ertech Construction Academy, which held its first course in 2008 with 15 school students from Clontarf.

In his trademark manner, Mr Giumelli made it happen by rustling up support from other people in the industry.

Land developer Stockland apportioned some land at its Stockdale project, WesTrac supplied some used equipment, and companies such as Humes and Rocla supplied pipes.

“Ertech underwrote that all the way through to 2018, to the tune of nearly $4 million,” Mr Giumelli told Business News.

“We had about a dozen graduates every year.”

Mr Giumelli has retired from Ertech, which, under his leadership grew to be one of the largest privately owned contractors in Western Australia.

But he’s not the retiring type, with his energies now focused on building up the training academy.

His motivation has not changed in 15 years.

“There was a shortage of labour, just like now,” Mr Giumelli said.

“The indigenous kids who have good eye-hand coordination were a potential source of labour.

“We can give them a future.

“The third thing was giving back to the industry that has been very successful for me and Ertech.”

Having decided to get serious about the training academy, Mr Giumelli formalised its structure by establishing a registered charity, known as the Motivation Foundation.

In its first year of operation, 2019, it had 15 graduates.

It has since grown rapidly. Last year, it had 52 graduates from its West Swan facility and a further 28 from its Collie academy, which it runs in conjunction with WesTrac’s technology training centre.

Foundation chief executive Tim Hunter describes the training academy as an industry self-help program.

It supplies new workers for a sector that, like many others in WA, struggles to retain experienced operators, who are often lured by the big dollars on offer in mining.

Mr Giumelli believes the model could apply to any industry.

“On the Kwinana industrial strip, if the boys there got together, they could do a similar thing based on their industry, it could work,” he said.

While the foundation delivers benefits for industry, it is focused on delivering outcomes for its students, most of whom come from poverty or are at risk of dropping out of school.

“We choose the students not based on their highest marks, [but] who we can make the biggest difference to in their life trajectory,” Mr Hunter said.

“We spend a lot of time with students when we first meet them.

“We also put them in a machine and let them burn some diesel and push some dirt around.”

Mr Hunter said the foundation’s program had been transforming for many of its graduates.

“It’s all about the attitude,” he said.

“It’s the coaching and the mentoring.

“Skills can come, we focus on behaviours.

“Turn up on time, be well presented, have a go, and pass our drug and alcohol test.”

Mr Hunter added that the program was focused on getting the students into jobs, with completion rates and employment rates in the high 90s (per cent).

“We focus on the jobs, it’s all about the employment outcomes,” he said.

“We are not finished until they are employed.”

With starting salaries of $60,000 a year in Perth and $130,000 per year if they go to the Pilbara, the foundation has had four graduates in the past two years buy a house.

“That’s four graduates from poverty or distress buy houses for their family so their mum and their brothers and sisters can live there.”

The foundation’s graduates include one student, Jesse, who won the Beazley Medal as the state’s top VET student in 2018.

“Jesse was a straight D student at school, but once he found his pathway he became a straight A student, because he knew where he was going and he was engaged,” Mr Hunter said.

He contrasted Jesse’s plans with another WA student who won the Beazley Medal as the state’s top ATAR student in the same year.

“She is going to be a doctor, but Jesse will earn a million dollars before she graduates,” Mr Hunter said.

Demand

Based on its track record to date, the foundation is looking to expand.

Mr Hunter said there was no shortage of prospective students.

“There is a long line out the door, that is easy,” he said.

“We are saying ‘no’ to young people who could do with our course.

“But it’s not just training them.

“We could train 500 but do they get a job at the end or is it a sausage factory where we hand out certificates?”

The pipeline of prospective students is helped by the foundation’s relationship with another Perth charity, Youth Futures.

It provides a range of services for at-risk youth, including crisis accommodation and education, and training for students who do not fit well in mainstream schools.

Youth Futures has opened a community trade school that operates in partnership with the foundation’s training facility at West Swan.

Mr Giumelli is focused on attracting more support for the foundation, which has built relationships with a wide range of industry groups.

“We have good connections with the mid-tier contractors in Perth,” Mr Giumelli said.

“We encourage them to donate $5,000 per placement, so we can use it for next year’s cohort.

The foundation also asks chief executives to donate scholarships to support future students.

WesTrac – whose chief executive Jarvas Croome sits on the foundation’s board – continues to provide mostly in-kind support.

Ertech also provides support, including used equipment and a $100,000 donation each year.

Mr Giumelli is hoping to sign up more corporate supporters, ideally covering different market segments, such as civil contracting, land development and mining.

He is also hoping for more backing from the Construction Training Fund, which is already a substantial supporter.

Mr Giumelli believes the foundation can help the CTF solve one of its major problems.

“They have all this money from the mining industry and the miners are asking what they can do with it,” he said.

The CTF collects a 0.2 per cent levy on all construction projects in WA valued at more than $20,000.

Its coverage expanded in 2018, when the McGowan government extended the levy to include projects in the resources sector.

That move, combined with the current boom in residential construction, has significantly boosted the CTF’s revenue. Levy payments have jumped from $25.2 million in 2018 to $45.8 million last year.

They are expected to decline this year to $37 million, but that is still above historical norms.

The money is used to subsidise training and apprenticeships across the construction sector.

This includes scholarships for year 11 and 12 students doing trade certificates, a program that had been utilised by the foundation.

“We do ‘cert two’ in civil construction and in resource and infrastructure,” Mr Hunter said.

“It’s essentially a pre-apprenticeship in civil and mining.

“We have graduates trained in the basics of mining and going into mining; 10 out of 80 last year.

“We are showing the CTF a return on their scholarships with us for the mining industry and we would be the only ones doing that.”

CTF chief executive Tiffany Allen, tasked with disbursing the funds, acknowledges several challenges.

She believes some contractors in the resources sector do not have a culture of training or are not fully aware of how the CTF operates.

“It’s an education about how best to use the levies,” Ms Allen said.

One part of that is explaining how much is available: up to $21,000 per apprentice.

Another part is explaining who is eligible.

On a big resources project, the mining company will typically pay the levy but it’s their sub-contractors that can claim the training subsidy.

“We need to get deep into that sector to make them aware they can come and get the subsidy,” Ms Allen said.

“If any of them employ an apprentice during the construction component of the project, they can claim the subsidy.”

That definition creates its own challenges, as apprentices working in operational roles or on routine maintenance are not eligible.

They need to be engaged in construction work, which can include major refurbishments.

Former Chamber of Minerals and Energy of WA chief executive Reg Howard-Smith now chairs the CTF board.

That’s quite a turn, as the mining lobby had for many years opposed the extension of the levy.

Ms Allen said she had held many meetings with the CME to spread the word about the CTF and what it could do.

Over the past financial year, the CTF made payments to the employers of 2,596 directly indentured apprentices.

In addition, it supported the employment of 1,445 apprentices employed by group training organisations, such as Carey Group Training, MEGT, Directions Workforce Solutions and Skill Hire.

It has also provided funding for try-a-trade courses for school students and introduced a program to subsidise the wages of mature-age apprentices.

The CTF programs are in addition to multiple state government initiatives designed to boost the number of people in apprenticeships and traineeships.

The latest data shows these initiatives are having an impact.

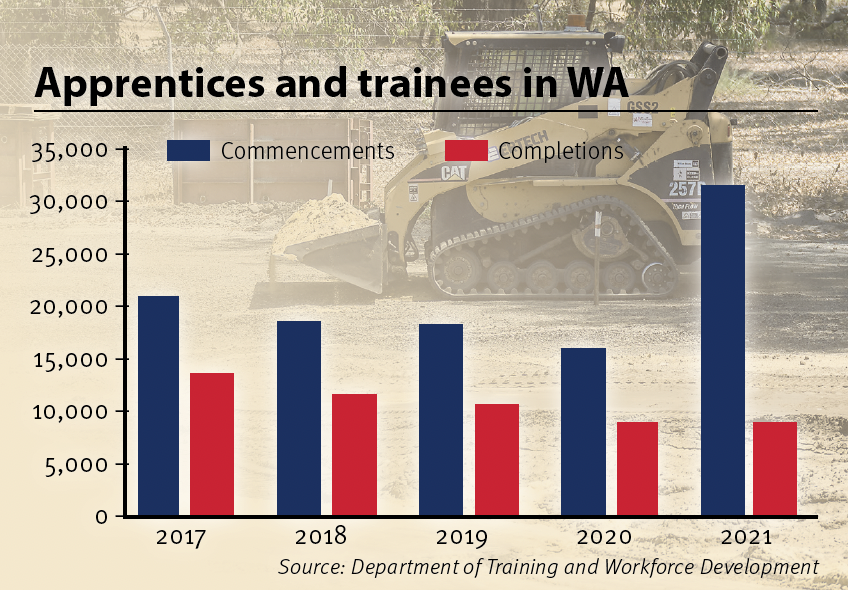

The number of people starting apprenticeships and traineeships nearly doubled to 31,787 in the year to September 2021 (see graph).

However, this was off a low base.

The lack of investment in apprenticeships and traineeships in recent years is shown by the decline in the number of completions, to about 9,000 in each of the past two years.

Ms Allen has developed a range of strategies to bolster training in the construction sector, including campaigns to change the perception of construction as dirty and dangerous.

She is also keen to raise awareness of what she calls ‘para-professional trades’.

“We cover project management, environmental design, accounts scheduling, estimating,” Ms Allen said.

“They are all components of our industry, but they are not seen as trades.”

She also wants to promote a more diverse workforce to make construction trades more attractive.

“It is very male dominated,” she said. “It’s 14 per cent females in the entire construction industry but only 2.5 per cent in the trades.”

The push for diversity includes making trades more accessible for Aboriginal people, especially on-country.

That’s one area where the Motivation Foundation believes it can make a difference.

About 20 per cent of its students are Aboriginal and Mr Giumelli sees opportunities to take on more by expanding to the regions.

He names Bunbury and Peel as two regions the foundation wants to target.

“Kalgoorlie is on our radar too,” Mr Giumelli said.

Mr Hunter described Kalgoorlie as an area of need.

“It has labour shortages, and it has disengaged youth,” he said.

“You put us in the middle and that’s the model.

“Kalgoorlie is easy, we know the jobs are there, we know the companies.”

Setting up a training academy is not a cheap exercise for a relatively small organisation like the foundation.

“To get Collie going, we had to spend $250,000,” Mr Hunter said.

Most of that money came from Mr Giumelli’s family foundation, which made a big donation to get the Collie facility going.

Everything the foundation has achieved so far has been done without any direct government support.

It has applied for some grants, most recently a regional development grant, but was not successful, much to Mr Hunter’s ongoing surprise.

The foundation has also had to fight local councils for planning approvals.

Despite the challenges, Mr Giumelli is energised and enthusiastic.

The foundation is taking on more students and its total revenue has grown rapidly, to about $1.2 million last year.

One loose guide to the foundation’s potential comes from the charity he supported 15 years ago.

The Clontarf Foundation kicked off in the year 2000, when a pilot program with a budget of $35,000 was launched.

By the year 2007, Clontarf had grown to about 750 students.

Fifteen years on, it has about 9,300 students spread across 138 academies around Australia.

Clontarf also boasts an impressive track record on student outcomes.

Out of 771 year 12 graduates in 2020, 88 per cent were either employed or engaged in further study in December 2021.

That helps to explain why Clontarf has attracted big licks of funding from governments and corporates around Australia, to the tune of $56 million last year.