WA’s planned exit from coal power comes with many challenges and significant costs.

Amber-Jade Sanderson has positioned herself as one of the state’s great optimists.

Having spent four years running the state’s health system, she is now in charge of Western Australia’s energy transition, including the planned exit from coal power by 2030.

Despite growing doubts in industry, Ms Sanderson, the energy and decarbonisation minister, said the government was committed to exiting coal by 2030, and insisted there was a clear pathway for WA’s energy transition.

Speaking recently at a sod-turning to mark the start of construction at the Warradarge wind farm expansion, she doubled down on her predictions.

“It is among more than 9,800 megawatts of renewable energy, storage and gas projects that will provide the power required by 2029-30 to support the state’s closure of coal-fired power stations,” Ms Sanderson said.

That mammoth undertaking represents about 10 times the total capacity added to the South West Integrated System (SWIS) during the past decade.

Business News has spoken to numerous energy experts and aspiring project developers; the feedback was almost unanimous.

Anything is possible if you throw enough money and people at it, but nobody sees this as a credible task.

Independent energy consultancy EnergyQuest shared that assessment, concluding that coal power will be needed beyond 2030.

“In the absence of evidence to the contrary, we assume renewable energy growth will continue to be slower than anticipated,” its latest report on the WA energy market concluded.

“Recent discussions with market participants in WA indicate a consensus view that some coal power generation will need to continue for a period beyond 2030 to ensure reliable electricity supply in the SWIS.”

The Australian Energy Market Operator, which manages the SWIS, expects that 1,695MW of ageing coal and gas power stations will be retired between 2027 and 2032.

This includes the Pinjar gas power stations and the privately owned Bluewaters coal power station.

The Bluewaters assumption is based on uncertainty over its coal supply, with a $220 million annual state government subsidy to Griffin Coal set to expire in June 2026.

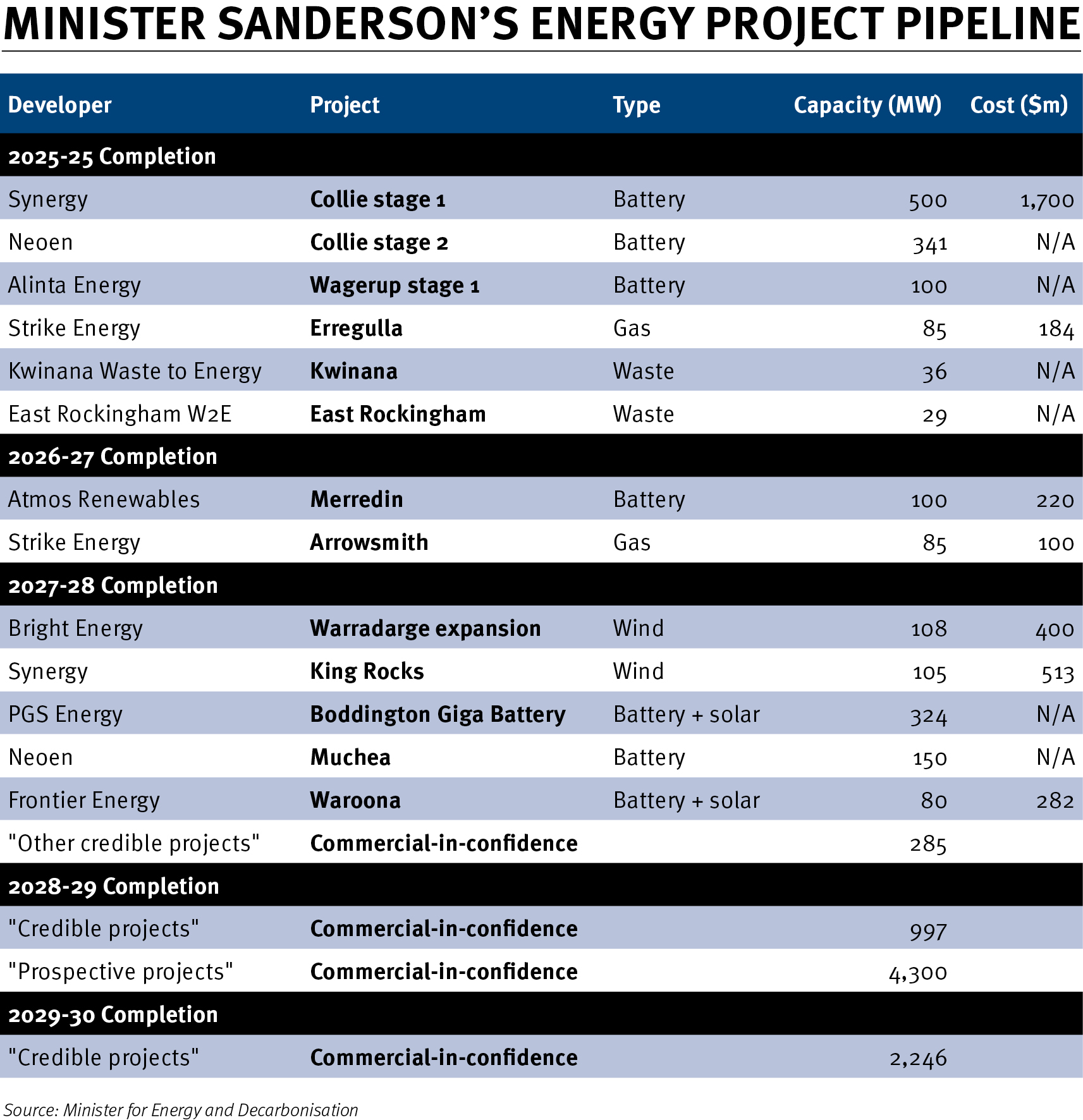

Against this backdrop, Ms Sanderson has drawn on confidential information compiled by the WA government’s Energy Coordinator to map out the pathway she anticipates (see table).

“In 2025-26 and 2026-27, over 1.2 gigawatts of new energy generation and storage will enter the market, with 200MW coal at Muja C scheduled to exit in 2025-26,” she said.

“In 2027-28, over one gigawatt is expected to enter, with 746MW of that funded by state or Commonwealth government and a remaining 285MW in other credible projects.

“This will replace 340MW at Collie Power Station scheduled to retire.

“In 2028-29, we expect 997MW worth of credible projects to enter the market, with a further 4.3GW in prospective projects that still have time to come online.

“In 2029-30 we expect 2.2GW in credible projects to enter the market, replacing 454MW of coal retiring at Muja D.

“These numbers are not hypothetical; they are based on real market intelligence and broadly line up with the independent work recently released by AEMO.”

Business News has challenged the minister on her predictions, submitting the following questions: “Is [the minister] seriously saying that all these projects can be planned, approved, financed, built and connected to the network in four to five years?

“And that the required network upgrades can be completed in this time frame as well?”

In response, the minister outlined steps the government is taking.

“We are developing the energy grid of the future with new transmission lines, battery storage, and wind, solar, and gas generation where needed,” she said.

“Significant work has been conducted in planning for transmission upgrades, with the results to be released later this year, assisting industry and proponents with their planning.

“We are supporting new-generation projects through government-owned utilities, such as Synergy and the Water Corporation.

“Working with the Commonwealth, we are supporting more generation projects to ensure that we have the capacity not only to meet existing demand, but to meet the demand of the future.

“At the same time, we are consulting with industry to understand what is needed from our energy supplies to ensure WA remains an internationally competitive place to extract, process, and use our natural resources.”

Ms Sanderson also referred to changes to the environmental assessment process and planning guidelines.

Battery flood

To understand the magnitude of WA’s energy transition task, it’s useful to start with a look at how much has been spent already.

The big-ticket investment so far has been in battery energy storage systems (BESS), which are designed to charge up when the wind is blowing and the sun is shining, then release power to meet peak demand.

About $6 billion has already been spent or committed on BESS, according to Energy Policy WA’s coordinator of energy Jai Thomas.

Getting to this number is not a simple exercise.

While WA Treasury’s budget papers disclosed that $2.5 billion will be spent by Synergy on its batteries at Kwinana and Collie, the cost of others is opaque.

Batteries being built by Neoen and Alinta have been procured by AEMO and are effectively underwritten by ‘availability payments’ to be made in future.

Four more BESS projects have attracted support from the federal government under its Capacity Investment Scheme, which guarantees a minimum return to the developer.

The first of these was Atmos Renewables’ Merredin battery, construction of which started last month.

PGS Energy, Neon and Frontier Energy aim to follow.

Mr Thomas got around these complications by making an estimate based on CSIRO’s average generation cost values and the size of the facilities being built in WA.

Speaking at a recent Committee for Economic Development of Australia conference, he described the big investment in BESS projects as a “uniquely WA success story” and “an incredible foundation to build on”.

The government insists the $6 billion investment in big batteries is warranted, pointing out that renewable energy is already the largest power source in the SWIS.

For the record, renewables provided 38 per cent of power in 2024, ahead of coal (29 per cent) and gas (33 per cent).

Industry sources who have spoken to Business News are not so positive.

They are concerned that WA has spent too much, too soon, on big batteries.

The minister’s own project pipeline highlights the big weighting toward BESS projects.

Of the 2.3GW she expects to come into the market in the next three years, about 1.6GW (70 per cent) comprises BESS projects.

That is additional to 544MW of BESS projects already built by Synergy and Neoen. In contrast, just two wind farms are under construction in southern WA.

These are Synergy’s King Rocks project in the Wheatbelt and an expansion of Bright Energy’s Warradarge wind farm in the Mid West.

Like batteries, new wind farms are not cheap.

The King Rocks and Warradarge projects will cost about $900 million and add 213MW of installed capacity.

Neoen completed commissioning of its 341MW stage-two battery at Collie in July, adding to its 219MW stage-one battery.

Extrapolating from those numbers, each gigawatt of wind power will cost about $4 billion.

Like the $6 billion being spent on batteries, that cost will ultimately be borne by business and households.

Change needed

AEMO’s latest WA report acknowledged the introduction of grid-scale battery storage has helped the market meet peak demand but says changes are needed.

It found that peak demand is continuing to grow and is extending into the night, meaning additional supply until late evening will be required.

It found the grid-scale batteries being installed in WA will not be sufficient, as they are designed to supply power for periods of up to four hours.

“Additional longer-duration (six-hour plus) battery storage will help but alone will be unable to meet forecast growth in these sustained peaks without complementing them with additional energy-producing capacity (from solar farms, wind farms or gas generators) to sufficiently top them up,” the AEMO report concluded.

“Consequently, new energy-producing investment will be prioritised in this year’s Network Access Quantity process.”

Shadow energy minister Steve Thomas said the AEMO report confirmed the opposition’s long-standing view that more investment was urgently needed.

Transmission

Western Power will need to complete major upgrades before new wind and solar farms can access the network.

It is currently upgrading the northern transmission line, which runs from Perth to the Mid West.

This is a ‘brownfields’ upgrade to existing infrastructure and is therefore considered the easy bit.

Western Power is yet to begin ‘greenfields’ network upgrades to the south and east of Collie, where multiple new wind farms have been proposed.

Western Power has been allocated about $1.2 billion for its Clean Energy Link-North project, which runs from its terminal in Malaga to Three Springs.

It includes a new 132-kilovolt transmission line from Wangara to Neerabup, new terminals and upgrades to the existing network.

Contractors UGL, GenusPlus and Acciona have been awarded substantial contracts for this project.

The project will remove constraints that limit the ability of existing wind farms to operate at full capacity.

More significantly, it will allow a further 1GW of new renewable energy to join the network.

Wind farms that will tap into the upgraded northern network are led by the expanded Warradarge facility.

Proposed projects that could access the network include Tilt Renewables’ Waddi wind farm, Atmos Renewables’ Parron wind farm, and Alinta’s Marri wind farm.

Wind zones

Ms Sanderson has noted the increased capacity coming into the northern line is more than the output from the two largest state-owned coal-fired power stations.

That implies one is an easy replacement for the other.

The reality is more complex; coal power stations can operate continuously, whereas wind farms are weather dependent.

The power from wind farms is needed most when the temperature is searing hot, yet those are the days when there is no breeze.

That is why wind farms need to be backed up with battery storage and gas power stations.

The impact of variable weather can also be mitigated by having clusters of wind farms in different locations, such as the Mid West, the South West and the Wheatbelt.

There is no shortage of developers wanting to build wind farms and, in a few cases, solar farms in these regions.

Business News’s projects database lists at least 20 wind farms in various stages of planning.

They are backed by highly reputable and experienced operators including Collgar Renewables, Acciona, Neoen and Sumitomo-backed Quenda Wind Power.

Western Power data also highlights the keen interest in building new wind and solar farms in WA.

It recently disclosed its pipeline of connection-ready projects as of June 30 was 12.8GW.

Cost blowouts

Major upgrades to Western Power’s network will need to be completed before these projects can tap into the network.

The news from other states indicates this will be a costly undertaking and may not be achievable before 2030.

A panorama of Warradarge.

AEMO’s 2025 Electricity Network Options report, released last month, found the cost of building new transmission networks had increased during the past two years, by 100 per cent in some cases.

It said the big jump in costs reflected supply chain pressures, project complexity and the need for additional community and landholder engagement along highly contentious routes.

The VNI West transmission project between Victoria and NSW is a prime example.

Transmission Company Victoria disclosed last month the cost had more than doubled to about $7 billion.

It also disclosed the completion date has been pushed back from 2028 to 2030.

“The new construction completion target allows more time for detailed environmental, geotechnical and cultural assessments, along with more meaningful landholder engagement on access and easement arrangements,” it said.

Other projects facing cost blowouts and delays include Project EnergyConnect linking South Australia to NSW, the Marinus Link from Tasmania to Victoria, Humelink from NSW to Victoria, and the Copperstring project in Queensland.

For the most part, WA has not yet experienced the pushback that’s a feature in communities up and down the east coast.

The construction of overhead transmission lines through prime farming land in the South West could change that.

Add multiple wind farms, each with dozens of wind turbines more than 200 metres tall, and the South West could resemble the politically charged flashpoints on the east coast.

This issue may be mitigated to the extent that new wind farms are built close to existing transmission lines.

Neoen, for instance, said there was a high voltage transmission line located at the southern boundary of its proposed Narrogin wind farm.

Offtake deals

Assuming all the challenges discussed above can be overcome, there are still two big hurdles standing in the way of the government’s ambitious energy transition plan.

One is that wind farm developers typically need to sign offtake deals before they can secure finance for their projects.

The Flat Rocks wind farm near Kojonup, for instance, proceeded only after the developer signed a power-purchase agreement with mining giant BHP in 2022.

Only a handful of other companies are sufficiently large to warrant signing a similar PPA.

Government utilities are another option, but Synergy is building its own wind farm and Water Corporation is pursuing development of its own wind farm at Flat Rocks.

This issue is not unique to WA.

A recent review of the east coast energy market, chaired by Griffith University’s Tim Nelson, proposed the creation of standardised contracts backed by government to facilitate the financing of new projects.

If a solution can be found to the offtake and funding issue, one further challenge remains.

Is it realistic to think WA has the capacity to build, say, 2,000MW of new wind farms in the next four to five years?

This task would require thousands of workers, many needing specialist engineering and technical skills.

And do WA’s ports and trucking companies have the capacity to import and transfer the giant components needed for each wind farm?

One industry source was in no doubt about the answer.

“There is simply no way that can physically be built,” they said.

“And even if it was remotely possible, the inflationary impact would be immense and lead to more cost blowouts.”